Two archive books

Themerson archive | Nick Wadley: archive

Jasia Reichardt, the instigator and main author of these two books, is the niece of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson (the artist [1907–88], and writer [1910–88] respectively). Both Themersons spent the first parts of their lives in Poland, up to 1938, when they moved to Paris; in the circumstances of war they emigrated separately to London, where they were reunited in 1942. After their deaths Jasia took their papers, books, materials – their archive – from the flat in Maida Vale where they had lived, to her house in Belsize Park. Gradually she made this catalogue, with help from a changing lot of helpers and assistants, and with her co-editor and late husband Nick Wadley. This work took around 20 years to do (though, as Jasia writes, it can never really be completed). These materials were then, in 2014, transferred to the National Library in Warsaw. At the same time she has been tireless in organizing a large and still continuing number of events, exhibitions, publications, which – judging by recent surveys of her times – are establishing Franciszka among the significant artists of Britain. How could one place Stefan among the writers and cultural contributors of his adopted country? British literary and intellectual culture presents severe barriers to work such as his.

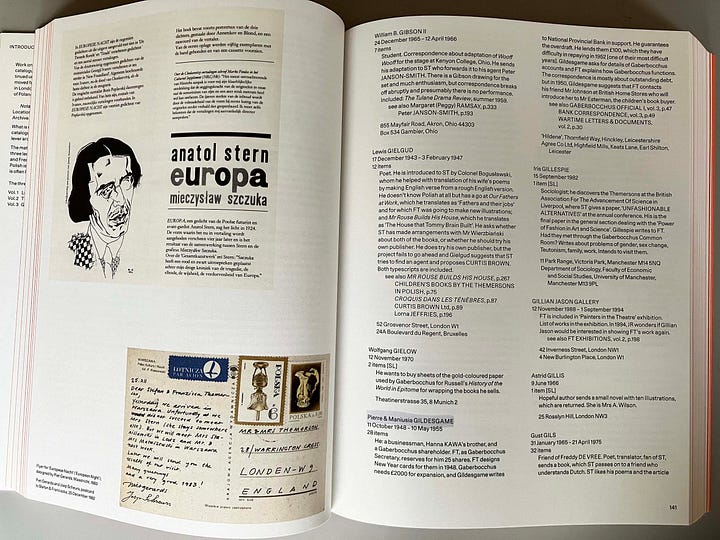

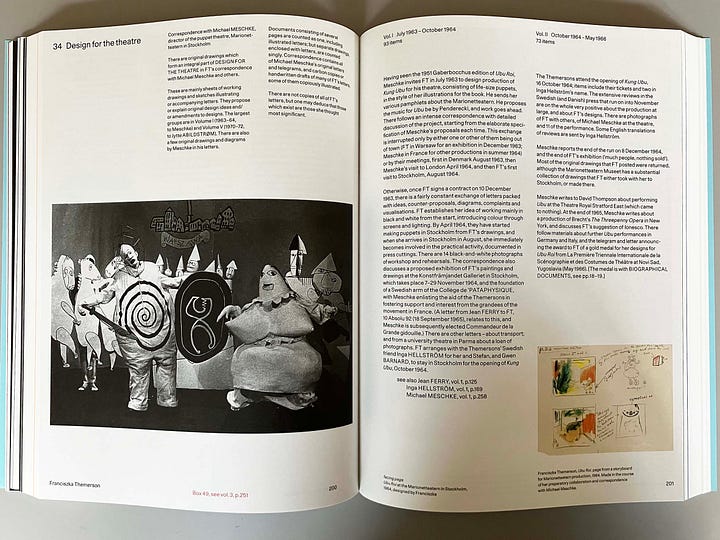

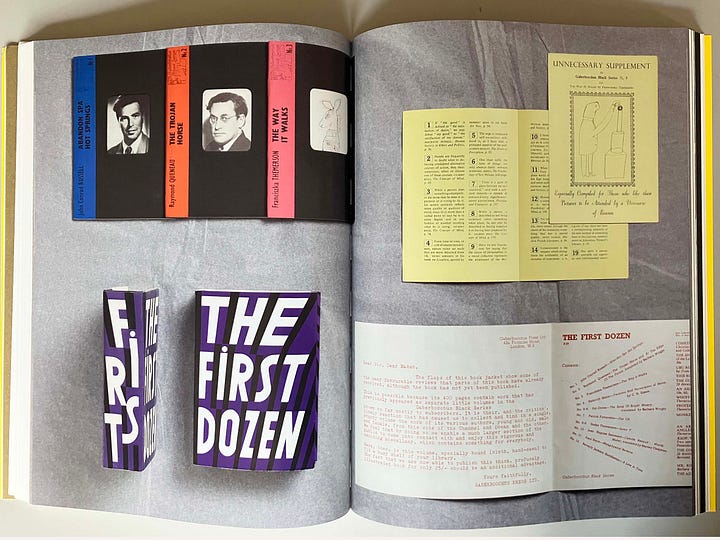

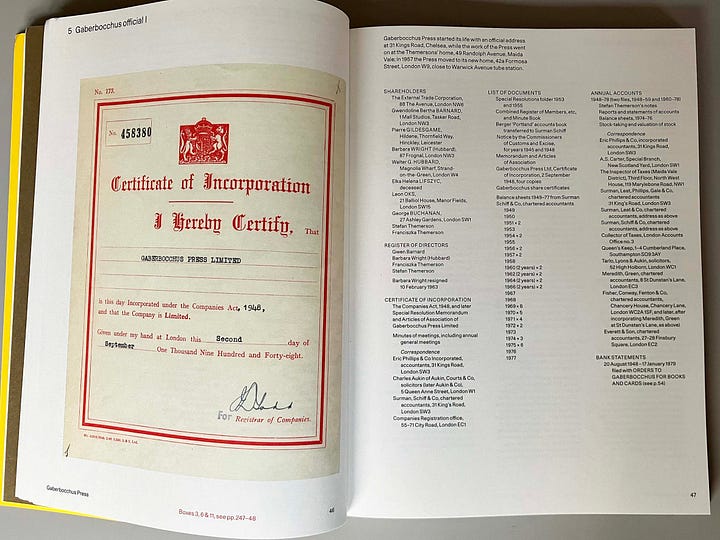

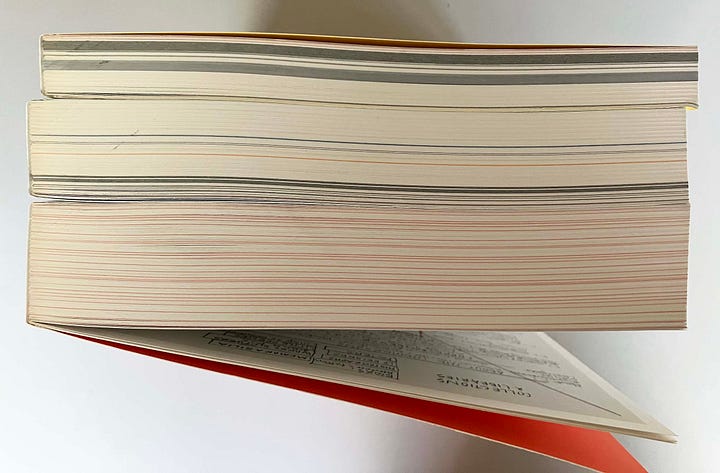

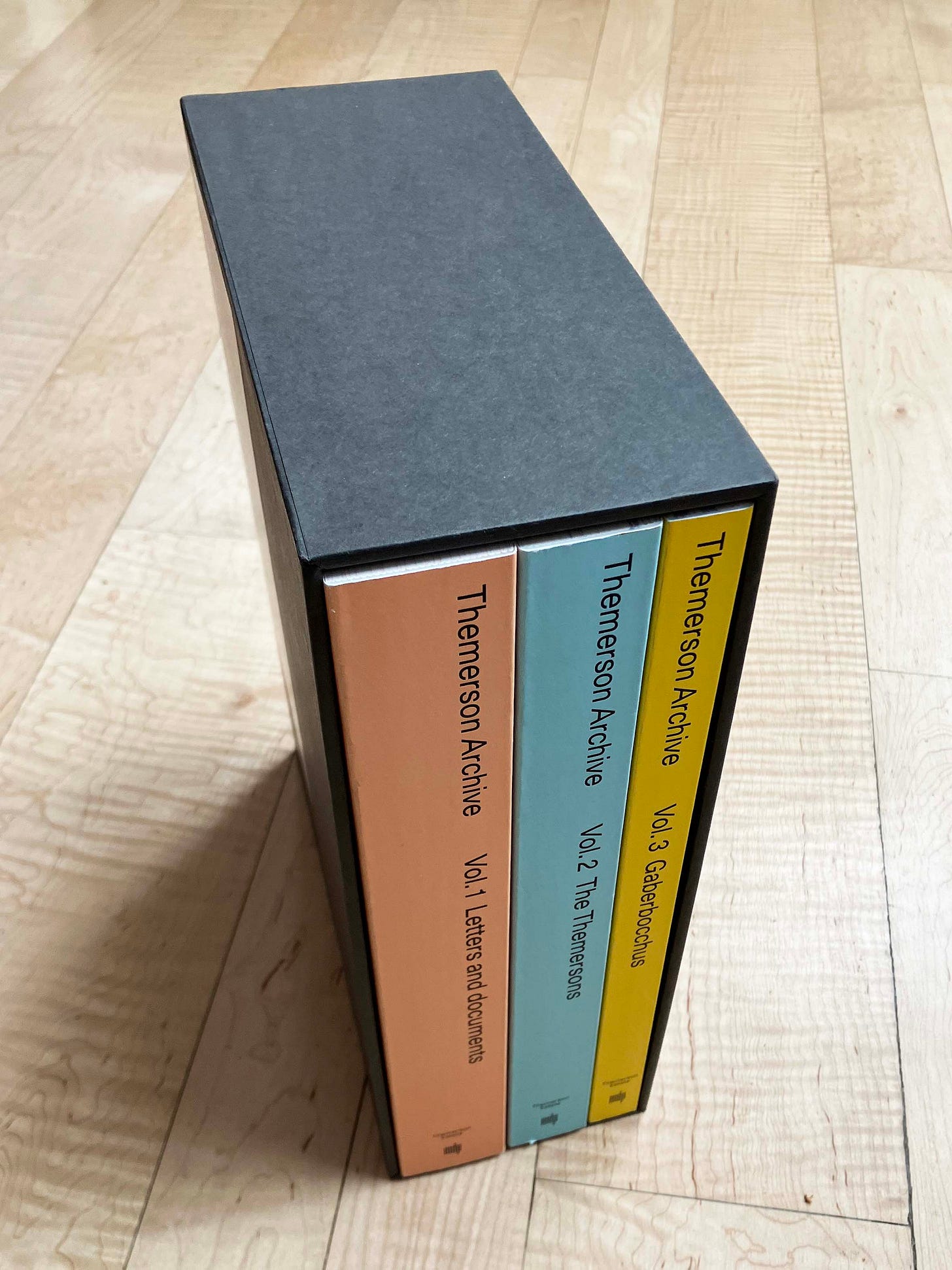

In 2020 the extraordinary three-volume Themerson archive was finished and published, edited by Jasia and Nick. A physical description comes first: 1044 pages (vol. 1: 472, vol. 2: 372, vol. 3: 260), page size 310 x 235 mm, and including the box in which the books are housed its weight is 5.8 kg. Volume 1 describes the letters and documents in the archive; volume 2 documents the life and works of each subject; volume 3 provides documentation of Gaberbocchus Press, which the Themersons ran from 1948 to 1979, publishing over 50 books.

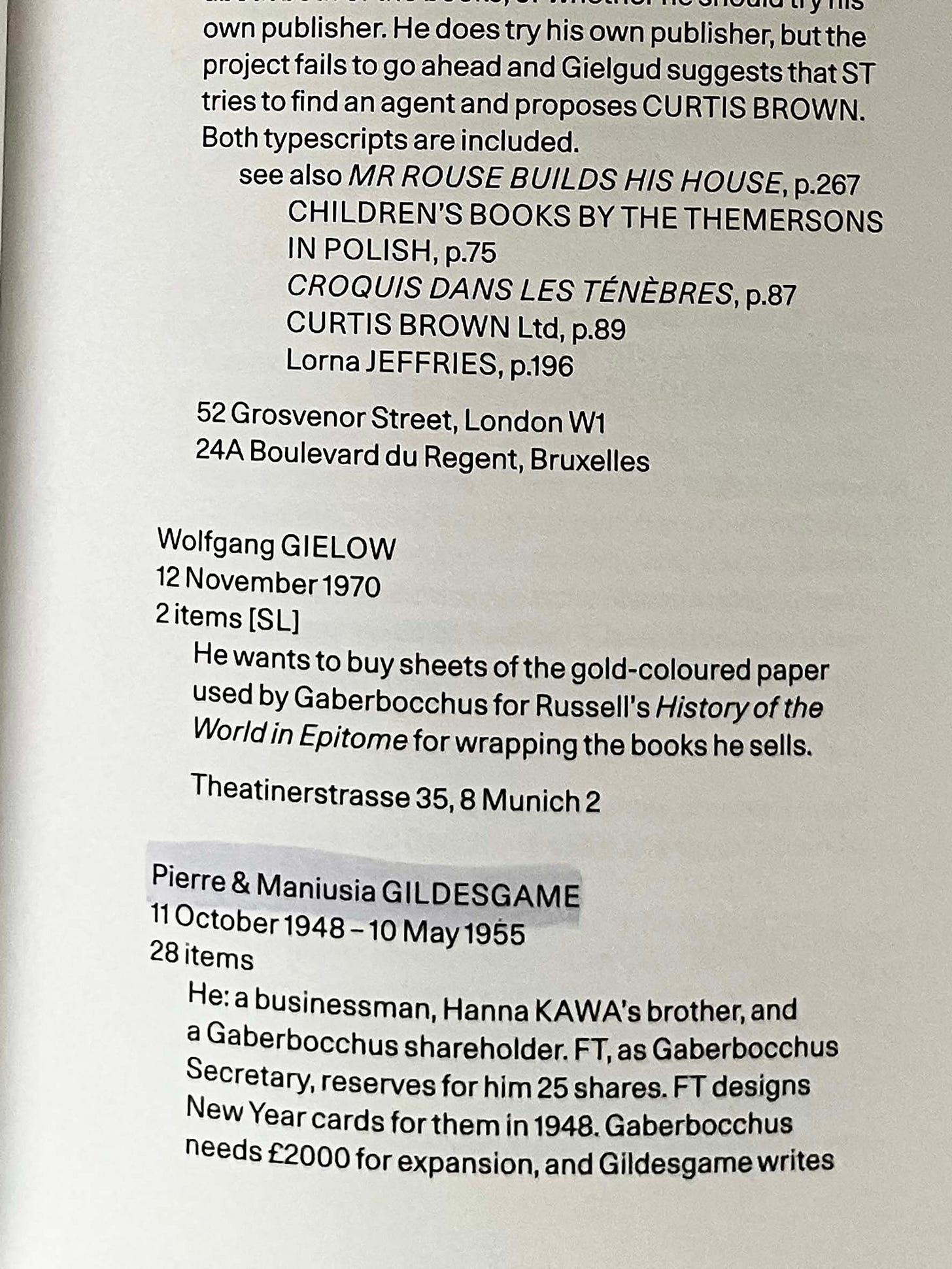

I have the sense that the materials here give us a lot more than a written biography ever could, and to which Stefan made principled objections.1 As well as all the listings and factual descriptions, many pictures of documents are included. These pictures, together with Jasia’s short and sometimes informal comments and ‘asides’, make for quite a lively book. One turns the pages with pleasure and in anticipation.

I should perhaps explain that I have some interest here, as a minor bit-part player in the story. In 1976, encouraged by Anthony Froshaug, I had a brief correspondence with Stefan when I was doing postgraduate research (on Otto Neurath and Isotype), and also bought some Gaberbocchus books directly from him.2 Later, after Froshaug’s death and when I was working on a book about him, I visited Stefan and Franciszka at their flat in Warrington Crescent. I wanted to re-publish the article on ‘the book as a means of communicating ideas’, which in 1946 Anthony had written for the journal Nowa Polska, and wondered if he had a copy of the original English text. Stefan had translated it into Polish for its first publication. He gestured to the crammed shelves behind him, which went up to the full height of the high-ceilinged room. He said that rather than try to find the text there, it would be quicker to translate it back into English from his Polish translation as published in Nowa Polska – and that’s what we did. Searching the archive book for a sign of Anthony’s original text, I can only think that it might be among the Nova Polska papers (vol. 1, p. 311).

Concerning the ways in which the book offers us its contents: it seems very clearly organized, and could be a model for anyone faced with cataloguing such an archive. Physically, the volumes don’t open well: sections of pages are stiffly glued and the outer spreads in a volume have to be held open with hands.

Themerson archive was designed by Pedro Cid Proença, with Teresa Lima, and printed and bound in Amersfoort by Wilco. The size of type used for the text struck me as large when I first saw it, but I got used to this, and if the pages are of this size, then it follows that the type needs to be proportionately large.

One detail to point out: ‘Where there is a particularly significant statement or piece of information, it is highlighted in blue for Stefan or orange for Franciszka.’ So some lines of text are given these apparently freely applied patches of transparent colour, as if someone has been there before us, going through the book with a highlighter pen. This does bring some sense of variety, something extra, to the pages – and it’s good that fluorescent ink hasn’t been used.

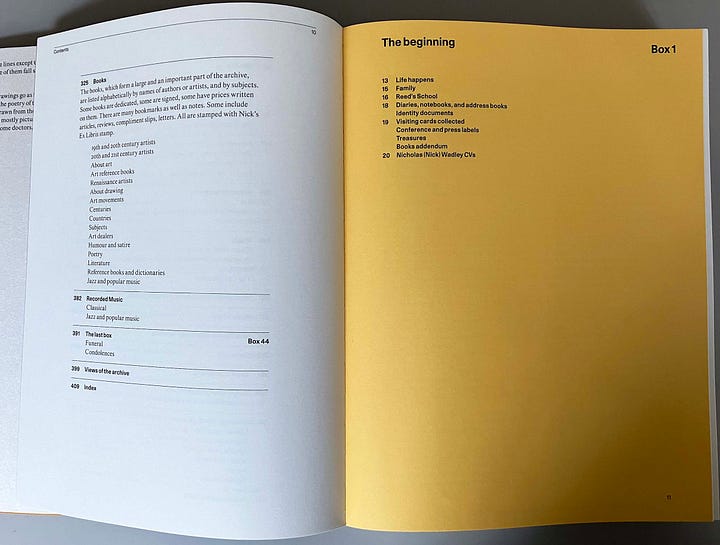

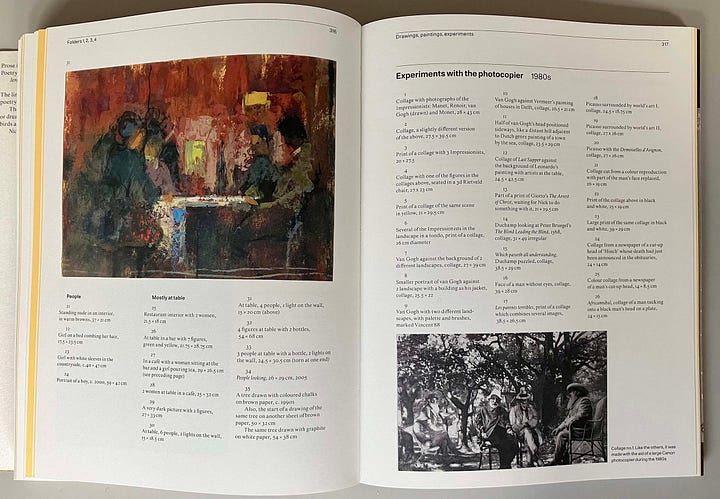

Jasia Reichardt’s second archive book provides a catalogue to the archive of Nick Wadley (1935–2017), now housed at the Tate Archive in London. In her introduction to the book, she writes (p. 6): ‘The catalogue attempts to give complete information about the contents of the archive. Its purpose is to facilitate decision if it would be a good idea to visit the archive and see the original documents.’

It’s a substantial work: 424 pages, page size 280 x 210 mm, 1.5 kg in weight. I count three different papers used within the book, plus endpapers, card cover material, and a wraparound sheet of slightly sparkling Japanese-type paper that has the title text impressed into it. These materials are delicately and expertly deployed, especially the sand-coloured sheets that introduce the pages devoted to each of the boxes of the archive and whose number is constrained by the restrictions of how the sections have to be gathered and bound.

Pages are mostly bound in sections of 16, sewn, cold-glued, and then given an Otabind (in my copy the front cover has come unstuck – no matter). Like the Themerson archive book, it was made at Wilco in Amersfoort, and was designed by Pedro Cid Proença.

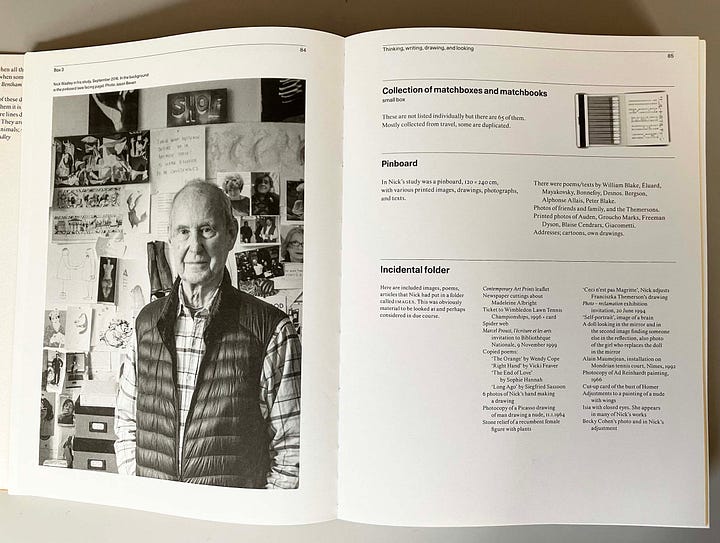

This is very clearly a labour of love. Nick Wadley was a quiet phenomenon: writer about art, and historian of art (especially the French Impressionists), a teacher (principally at Chelsea School of Art), a painter, and – increasingly in his later life – a drawer. As his funeral announcement in the Guardian said, he was ‘a lovely man’. He and Jasia Reichardt married in 2005. The book is published by the Waterlily Press, an imprint that Nick established for some of his own books of drawings. So it was written and published by its editor, with complete control over the contents. My copy was a gift from her.

I knew Nick very slightly, mainly in meetings with Jasia, though I first set eyes on him at a public meeting in the Conway Hall in London, in the early 1980s. This was a time of disruption in the English art schools, when rather free and informal old institutions were being brought into pseudo-academic polytechnic and then university structures. In a note in this book (p. 30), Nick wrote that he ‘took a very active role in a long series of protest meetings at County Hall and elsewhere across London. By 1985 I had decided this was no longer the way I wanted to spend my life, and I opted for premature retirement, which with immaculate timing took effect at the end of December 1985 (the day before the inauguration of the University of the Arts.)’

A note like this is fairly typical of what such an all-encompassing book may offer. You don’t know what you will find among its lists, its descriptions and quotations. For example, taken pretty much at random: Nick was drawn into the Collège de ’Pataphysique. Boxes 21 and 22 contain materials arising from this collaboration. In 2000 he organized the exhibition ‘UBU in UK’ at the Mayor Gallery in London. In her description of connected correspondence, Jasia summarizes (p. 190): ‘Ian MacFarlaine writes at length about his visits to cemeteries to find out where various famous people were buried. Jarry’s remains were removed from the original place of burial. Iain will return to his quest to be able to cross Jarry off his list. Barbara Wright is asked if she might know anything about Jarry’s grave but she doesn’t. Stanley Chapman takes up the correspondence …’ The description concludes: ‘Stanley reports that Barbara and Jill think Ian MacFarlaine is a nut-case.’

The listings conclude with a catalogue of books in Nick’s library, and then his collection of recorded music – LPs, tapes, CDs: classical (Bach to Kurt Weill and John White), jazz and popular (The Beatles through Krzysztof Komeda, Bessie Smith, to Stevie Wonder). Then box 44, the last one: ‘The three grey lever arch files in this box are about Nick’s health, or lack of it.’ (p. 393) The long index of names (pp. 411–23) is excellent.

Nick will never be the subject of a formal biography, but this book provides us with the elements of a biography, without the pretensions, fictions, and dubious assertions of that genre. Further – its lists of people, of documents, of objects have a kind of incidental poetry that belongs with the various spheres of culture that Nick was interested in and actually inhabited. As with the Themerson archive book, we can enjoy the explosions of fact and imagination in its materials.

Could these books have been websites, rather than printed books? Perhaps, and giving the material an online base would have acknowledged its unfinished nature, and overcome the problems of distribution and selling such books. But I am glad of Jasia’s commitment to the physical book. These works will outlast us all, in ways that websites certainly won’t. I have the idea that she is now at work on cataloguing her own archive. It should be a wonderful book.

Jasia Reichardt and Nick Wadley (editors), Themerson archive, London: Themerson Estate, 2020

Jasia Reichardt (editor), Nick Wadley: archive, London: Waterlily Press, 2022

Plus: Jasia spoke in 2022 about the Themerson archive book here; Jasia and Nick spoke in 2016 about the Themersons here.

Stefan outlined his objections to biography in comments on a short text that Anthony Froshaug once wrote about him: ‘I do not like that kind of literary research which consists in finding bits of author’s life & ad hoc connecting them with some bits of his work.’ (Anthony Froshaug: Documents of a life, London: Hyphen Press, 2000, p. 40.)

Jasia’s annotation (vol. 1, p. 207) describes me as a student of Froshaug’s, which I wasn’t.

Wonderful as ever Robin. This reminded me a little of the Wave books album style record of the Waldrops. https://www.wavepoetry.com/products/keeping-the-window-open